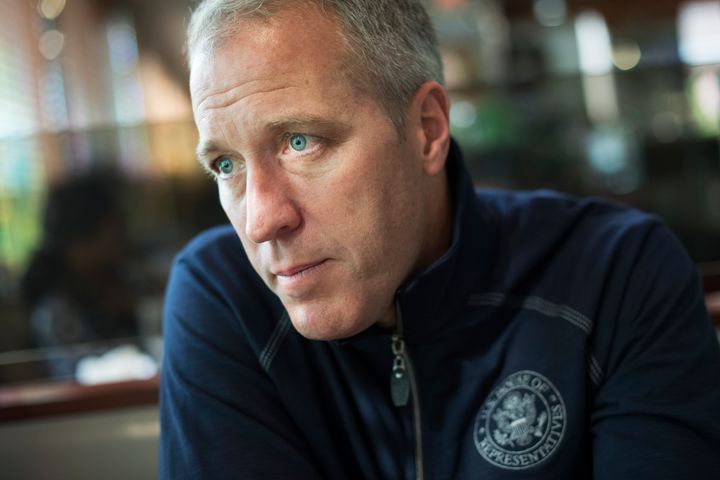

When Rep. Sean Patrick Maloney (D-N.Y.) realized his office didn’t have tampons for female employees and visitors, he ordered a bunch ― the same way he orders other basic supplies like paper towels, Band-Aids and hand sanitizer.

Maloney submitted receipts for his expenditures to the finance office of the Committee on House Administration for reimbursement. This week, he received an email stating that every purchase had been approved except for one ― the $37 he spent on menstrual hygiene products.

He was told that tampons are a “personal care” item, not an “office supply” item, and that he had to cover the cost of the tampons. Maloney wrote the check and is now urging the committee to include tampons and sanitary pads in its list of acceptable items that government officials can buy using their allotted allowances.

Through this effort, Maloney’s joined a chorus of activists who’ve been pushing for menstrual hygiene products to be viewed as a basic necessity that women shouldn’t be penalized for needing.

“It goes to the heart of who they think matters and whose needs matter,” Maloney told HuffPost. “It portrays a mindset that doesn’t see women’s needs as equal to men’s.”

The Committee on House Administration said in a statement that it didn’t send an email about the issue or provide guidance on this matter. The committee also didn’t indicate whether tampons are permissible to purchase with allowance funds. It just stated that it’s permissible to buy items that are “necessary health and safety products.”

In response to the statement, Maloney’s office released the text of the email it said it received from the committee.

Maloney noted that this was the first time ever that he was denied reimbursement for a purchase. While tampons were deemed off-limits, the budget, which is officially referred to as the Members’ Representational Allowance, permits government officials to buy a whole slew of less essential items, including embellished letter openers and wooden tissue holders, Maloney said.

Jennifer Weiss-Wolf, a leading advocate for menstrual equity, told HuffPost that this instance is just another example of how the government uses rules and legislation to exert control over women’s bodies. “This is outrageous,” said Weiss-Wolf, author of Period Gone Public: Taking a Stand for Menstrual Equity. “And yet another way that women’s bodies are devalued as a matter of policy.”

Maloney acknowledged that some might say he’s making “a big deal out of nothing.” But advocates agree that these conversations are critical to breaking taboos around menstruation and recognizing that this is a rights issue that disproportionately affects poor women.

Despite recent advancements, most people still don’t view access to feminine hygiene products as a basic right.

According to a survey of 2,000 people conducted by YouGov last year, 46 percent of men and 65 percent of women agreed that having access to affordable tampons and pads should be categorized as a right, not a privilege.

For many poor women and girls, these items are prohibitively expensive and remain a luxury they can’t afford. A box of 36 tampons typically costs about $7. Over the course of a lifetime, women spend about $2,200 on sanitary pads and tampons.

Low-income girls often miss school when they menstruate because they can’t afford pads or tampons. Missing a week of class per month can cause them to fall behind, face suspensions and possibly fail to graduate, which further perpetuates the cycle of poverty.

Some states are starting to take notice of this and do something about it. California passed a bill last year that requires schools to provide tampons and pads to underserved students. All Illinois and New York City public schools are obligated to provide these products for free.

Women incarcerated in federal prisons now get free tampons and pads, and state prisons may soon follow.

Managing a period is often one of the biggest challenges for women who are homeless. Menstrual hygiene products typically top the lists of the most-needed items at shelters. Part of the legislation passed in New York City in 2016 included providing menstrual hygiene products to women in shelters.

Advocates are also continuing to address how these items are taxed. In most states, menstrual hygiene products are subject to sales tax because they’re not considered a basic necessity the way medicine and food are. At least six states, including Minnesota, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Maryland and New York, do not tax menstrual products.

Maloney hopes his petition to the Committee on House Administration will help keep the spotlight on menstrual hygiene issues and propel the conversation forward.

“When you’re in Congress, sometimes little battles come to you that speak about big truths, and they’re worth having,” Maloney said. “If members of Congress don’t lead on this, who will?”